Along the western coast of Namibia, desert meets ocean with stark and beautiful suddenness. In the north, the white-capped surf of the blue-black Atlantic laps at the edges of enormous golden sand dunes. To the south, the dunes give way to rocky desert moonscape. Carved into that moonscape, at the edge of a small harbor, sits the remarkable town of Lüderitz.

Founded by German colonists in the late 19th century, Lüderitz was first a trading post, then a boom-to-bust diamond mining town, and now primarily a fishing village and ecotourism destination known for its colonial architecture and wildlife. It passed from German to South African control after World War I and then became part of Namibia when the young nation was founded in 1990.

Endangered seabirds gather off the coast of Namibia

If you were to board a boat in Lüderitz and travel 8 hours northwest, you would come upon a tiny island that you might mistake for a giant rock. Mercury Island, as it is named, is approximately one football field wide and five football fields long. It rises sharply out of the water to a height of 131 feet. It is hollow in the center, and when ocean swells crash inside the coves beneath it, the entire island shudders. It is arid, rocky, windswept, and seemingly inhospitable. And yet, it most certainly is not barren. Seabirds cover its surface. It is a loud and bustling bird breeding ground and home to several endangered species, including African penguins, Cape gannets, and Bank cormorants. In fact, this tiny island supports by far the largest colony of African penguins in Namibia.

Mercury Island is one of about 20 islands off the coast of Namibia collectively known as the Penguin Islands. African penguins once nested on all these islands by the hundreds of thousands. Now, the Namibian population hovers around 5,000 breeding pairs, which are sorted into three main colonies found on Mercury, Halifax, and Ichaboe Islands. Small numbers of breeding pairs are also scattered on other islands and in a few coastal caves.

Two centuries ago, Halifax Island – an hour’s boat ride from Lüderitz – was covered in a layer of guano 120 feet thick. Guano is bird poop. It was also once known as “white gold” because of the price it could fetch as fertilizer. Halifax and the other Penguin Islands have long since been scraped clean of guano, which means that penguins can no longer hollow out little guano caves to nest in. Instead, they mostly nest in the open on rocky ground. Kelp gulls and other predators easily pick off penguin eggs in open nests. Adults and chicks face other threats as well, including exposure to the elements, food scarcity, oiling (whether from a disastrous spill or illegal dumping), and disease.

Survival of a Species

Life is precarious for the African penguins of Namibia. There aren’t that many of them, and one catastrophic event could crash the population. At the moment, though, their numbers are holding steady while their biological importance skyrockets.

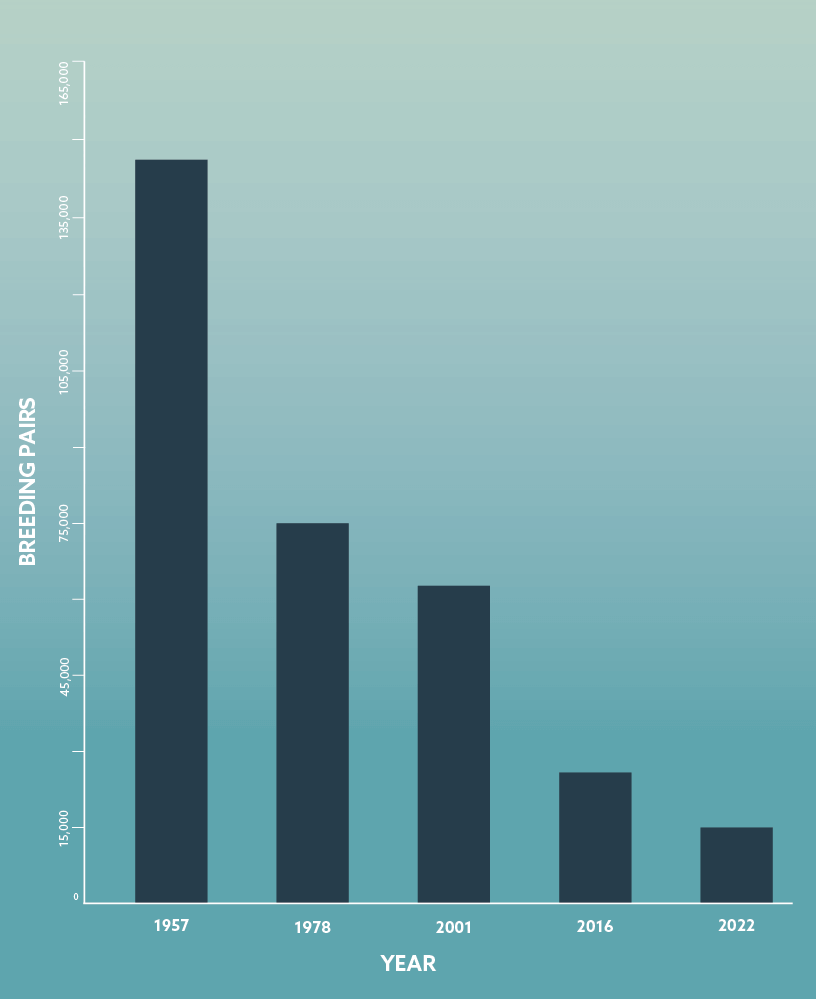

African penguins are native to only two countries: South Africa and Namibia. As of the 1920s, there were an estimated 1 million breeding pairs in the wild. That number has been shrinking ever since. Historically, the South African population has always dwarfed the Namibian population, but a significant shift is now occurring. Between 2019 and 2021, the South African population declined by nearly 25% to approximately 10,000 breeding pairs. With the South African population in freefall, the Namibian population now represents one-third of the global total.

Those penguins nesting on the string of islands protruding out of the ocean off the coast of Namibia could be the difference makers in the survival of a species.

Partnering to Save Penguins

Jess Phillips appreciates both the importance and the vulnerability of Namibia’s penguin colonies. He has been networking, corresponding, and brainstorming for several years now on how best to protect these penguins. They have lured him all the way from Baltimore to Lüderitz on three occasions over the past four years, and they are central to an inspirational, international conservation effort now unfolding.

Phillips is Area Manager of Penguin Coast and the Africa Barn at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. With institutional support from the Zoo, he also serves as vice-coordinator of the AZA SAFE African Penguin Project and coordinator of its Disaster Preparedness and Response Projects. Since 2017, he has been working with colleagues in South Africa, and particularly at SANCCOB (Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds), to put the necessary equipment, training, and manpower in place to respond quickly to any major disaster, such as an oil spill or disease outbreak, that might impact South African penguin colonies.

All the while, though, Phillips has also been focused on Namibia’s penguin colonies to the north. “Pretty much from day one of starting this position,” he says, “I was curious about what was going on in Namibia. I would ask, and none of my contacts in South Africa really seemed to know, so I thought we should find out.”

Phillips is Area Manager of Penguin Coast and the Africa Barn at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. With institutional support from the Zoo, he also serves as vice-coordinator of the AZA SAFE African Penguin Project and coordinator of its Disaster Preparedness and Response Projects.

In October 2018, after lining up private funding to sponsor the trip, Phillips and two colleagues from SANCCOB traveled to Namibia and spent two weeks meeting and talking with anyone and everyone involved in local penguin conservation work. What they learned was both encouraging and sobering.

“There’s a huge amount of awareness in Namibia for protecting the environment and wanting to do the right thing,” says Phillips. “Protection of wildlife and other natural resources is literally written into their constitution. The problem is, there’s just no funding, so there are people who want to do the right thing but don’t have the means.” As a result, he discovered, there was very little real protection in place for Namibia’s penguins.

During those two weeks in 2018, when Phillips broached the idea of partnerships and support from AZA SAFE to jumpstart penguin conservation efforts, the response was overwhelmingly positive. “Scientists, senior government ministers, NGOs, business representatives, everyone said YES!” he recalls. “And it wasn’t like, ‘Yes, please help us.’ It was like, ‘How can you help us do our jobs?’ Nobody wanted to sit back and watch us do everything. They wanted to jump on it themselves.”

AZA SAFE: Saving Animals From Extinction is a decade-old initiative of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) to leverage expertise and resources within the AZA community in support of already-existing in situ conservation programs around the world. Its approach is collaborative and supportive. SAFE participants build relationships with those doing the work in situ, determine jointly how best to offer support, and then bring resources and expertise to bear.

Putting Plans in Motion

One of the people Phillips met on that trip was a representative for De Beers, an international company synonymous with diamonds that has a tremendous business and philanthropic presence in Namibia. This De Beers-affiliated environmental officer was enthusiastic about the proposed disaster readiness and response project. She offered support for purchasing equipment and put Phillips in touch with the Executive Manager of the Debmarine-Namdeb Foundation. From there, things got very interesting very quickly.

The Debmarine-Namdeb Foundation is essentially Namibia De Beers Group of Companies philanthropic arm in Namibia. It seeks to partner with local communities to promote socio-economic development and advance sustainable projects and initiatives. Phillips struck up an e-mail correspondence with the Foundation’s Executive Manager, still intent on the immediate goals of purchasing disaster response equipment, drafting contingency plans, and training first responders. Then one day, while sitting in his office at the Zoo, he received an unforgettable phone call from the Executive Manager.

“She basically said, ‘We’re all in on this and we want to really make this a major project for the Debmarine-Namdeb Foundation and for De Beers in Namibia, and we would like to help develop a seabird conservation center and really get this up and running,’” recalls Phillips.

A seabird conservation center in Lüderitz, modeled after SANCCOB, the premier seabird conservation center in the world?

“I was astounded,” recalls Phillips. “I was absolutely flabbergasted.”

In that moment, the fate of African penguins and other endangered seabirds living off the coast of Namibia took a major turn for the better.

The Founding of NAMCOB

Phillips has returned to Namibia twice since 2018 – once in March 2020 and more recently in April 2022 – to meet with the near dozen partners and stakeholders now invested in this burgeoning conservation effort. Between visits, he has worked the phones relentlessly, maintained a steady stream of trans-Atlantic e-mails, and helped secure critical grant funding (including a recent award of nearly $30,000 from the AZA Conservation Grants Fund for the Halifax Island Ranger Project!)

A crowning success over the past two years – and a major step in the right direction – has been the creation of NAMCOB, the Namibian Foundation for the Conservation of Seabirds.

“Networking. The thing I love to do the most,” he says with a wry smile. Between check-ins with rhinos, penguins, and animal care teams at the Zoo, he networks for Namibia’s seabirds. “It’s been kind of crazy,” he admits, “but it’s also been very exciting.” All that networking is reaping success.

A crowning success over the past two years – and a major step in the right direction – has been the creation of NAMCOB, the Namibian Foundation for the Conservation of Seabirds. Modelled on SANCCOB, its South African counterpart and partner to the south, NAMCOB is a new NGO dedicated solely to the protection and conservation of Namibian seabirds. The Maryland Zoo is a founding member, along with SANCCOB, the Debmarine-Namdeb Foundation, Namibian Chamber of Environment, Namibia Nature Foundation, and the Namibia-based African Penguin Conservation Project. NAMCOB will work with the governmental Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources to monitor seabird colonies, protect habitat, ensure disaster preparedness, and promote community engagement and education.

Realizing a Vision

For now, NAMCOB is operating out of a small, refurbished seabird rehabilitation facility in Lüderitz. A project manager will be hired within the next few months, along with the first of several rangers who will live on the islands with the penguins and other seabirds and monitor the health of their colonies. Meanwhile, disaster readiness and response planning are well underway. Equipment has been purchased and stored, and more than two dozen Namibian first responders have already been trained at SANCCOB. Hopefully they will not have to put their training to the test anytime soon, but if needed, they are ready.

We are proud to be a founding member of NAMCOB, and proud of the work that Phillips and so many other dedicated staff are doing on behalf of wildlife and wild places in Maryland and around the world.

As for the new seabird conservation center, a site has been chosen just outside of Lüderitz, an architect has been hired, and the project is entering its design phase. Once completed in two to three years, it will serve as a model for conservation excellence in a country committed to the betterment of its people, its environment, and its wildlife.

Will the African penguins of Namibia be saved? Will the species survive? Those are hard questions to answer, but it is fair to say that they have a better chance of survival now. It is also fair to say that partnership, perseverance, and optimism are powerful forces in wildlife conservation. You can’t do this work without being an optimist, and the Maryland Zoo is full of optimists. We are proud to be a founding member of NAMCOB, and proud of the work that Phillips and so many other dedicated staff are doing on behalf of wildlife and wild places in Maryland and around the world.

BACK TO STORIES

BACK TO STORIES

MORE ZOOGRAM STORIES

MORE ZOOGRAM STORIES