The Giraffe House is currently closed for Kipi and her calf.

Shortly before his death in 2012, the renowned animal behaviorist and zoo consultant, Dr. Hal Markowitz, published his final work. Enriching Animal Lives represented the culmination of a decades-long career dedicated to improving the lives of zoo animals through environmental enrichment. It is effectively a recipe book for how to design and implement enrichment programs, along with a creative array of automated enrichment devices, for a wide variety of zoo animals.

“When I was introduced to that book ten years ago, I immediately felt that it filled a clear need for every zoo and aquarium I’ve ever been around,” says Joey Golden, the Maryland Zoo’s new Curator of Animal Behavior Programs.

Like Markowitz, Golden has a background in animal behaviorism and a penchant for creative design and bootstrap engineering. He draws inspiration from the automated enrichment devices that Markowitz invented (and is an inventor himself). He also shares the view that enrichment, broadly defined, is a means to empower an animal with choice, change, challenge, and control. An enriched environment goes beyond meeting an animal’s basic needs; it takes into account an animal’s natural history, stimulates natural behaviors, encourages mental and physical fitness, reduces boredom and stress, and thereby improves welfare.

Guided by Animal Behavior

Golden now has the opportunity to contribute to the enrichment of every animal at the Maryland Zoo. He joins a team of three at the Zoo that is led by General Curator Mike McClure and includes Animal Behavior Specialist Mandy Fahy. Together, they are in the early stages of building a zoo-wide program that McClure has been thinking about and working towards for years. Guided by animal behavior, it will critically assess and holistically improve upon how every animal at the Zoo interacts with its environment. This work will be done in full partnership with other animal care staff, especially the keepers who engage most closely and consistently with the animals.

“I’ve always wanted greater insight into animal behavior to drive training and enrichment programs, and I think it’s also important to remember that zoo animals have lives that are 24/7,” says McClure. “For me, successful exhibit design accounts for a species’ natural history and prioritizes individual animals’ mental and emotional life as much as physical comfort. And successful enrichment programs enable animals to feel safe, confident, and stimulated in their environments at all times, not just during the 8-hour window when staff and visitors are around.”

The Power of Observation

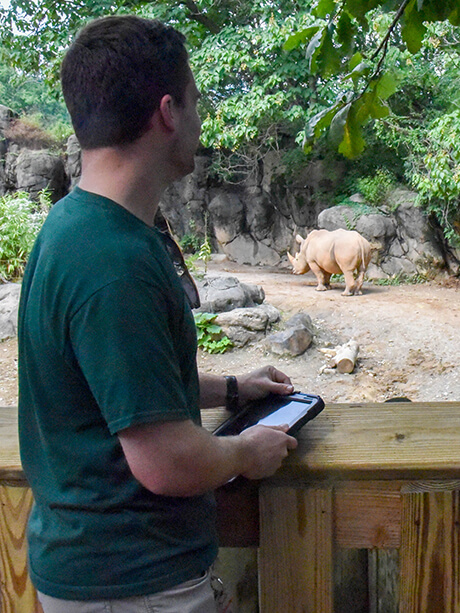

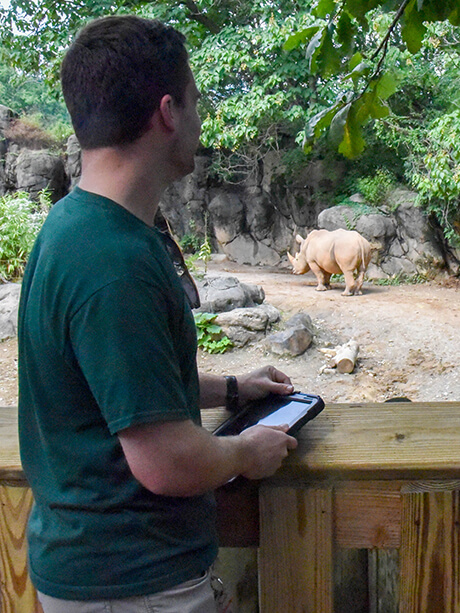

The starting point for this admittedly ambitious behavior program is to sit back and observe, and that is precisely what Golden and Fahy are doing now. It may sound passive, but it is anything but. Observing an animal over a prolonged period of time is an effective way to absorb what that animal is communicating. Golden explained it this way in a recent interview:

“You chose that seat when you walked in because it has more value to you than any other seat. You chose the central part of the table, you chose to sit opposite me, and you moved that box to get a more direct sight line. Every choice you made increased the value of that seat, whether you knew it or not, and you communicated that to me through action. You could have used words to explain your choices, but you didn’t. Animals can’t use words, but they can communicate the same type of information. By collecting all of that information – through behavioral observation – you allow animals to answer your questions about what they value.”

In other words, if you watch an animal long enough, if you log thousands of behaviors, and if you then discern patterns in those behaviors, the patterns become something akin to the animal’s “voice,” articulating what it values and what it does not. In a zoo setting, animals will reveal through their behavior how they value their physical space, enrichment opportunities, choices of activity, choices of company, and quite importantly, interactions with staff and visitors.

Portraits of Value

While sitting back and observing for the next several months, Golden and Fahy will actively tune in to what animals are communicating. They will pay attention to how individual animals are behaving on exhibit, behind the scenes, during training sessions, by day, by night, and so on. They won’t do it alone, of course; they will partner with animal care staff and with volunteer observers to build these books of knowledge.

Golden is quick to add that behavioral observation is no substitute for the knowledge that keepers internalize and intuit about the animals in their care. It is, however, a valuable enhancement to that knowledge. “Keepers know more about the animals that they work with than I ever will,” he says. “They are already 80% of the way there. I’m hoping we can provide that extra 10% that tells them something they didn’t already know, maybe something in the background that isn’t easy to notice. And then there’s 10% that will always remain a mystery.”

Case by case, as portraits emerge of what individual animals value in their environments, staff will tweak how they enrich that animal’s habitat, how they manage day-to-day husbandry tasks, and how they interact with that animal to create increasingly positive experiences. The possibilities for how the tweaks will play out are endless, but the bottom line is that the animals themselves will drive the process through their behavior.

The Case of Two Polar Bears

The best way to illustrate all of this is through a recent case study with two female polar bears then living at the Zoo. In May of 2020, both bears chose to spend their waking hours for three straight days swimming laps in the pool. The bears were not responding to repeated attempts to get them to engage in other behaviors. The team that cared for them became increasingly concerned, wanting to break them out of their circle-swimming but not sure how to proceed. McClure and Mammal Curator Erin Grimm stepped in to observe the bears, gain insight into the situation, and then give the team a new framework and understanding of what was going on.

“That circle-swimming in the pool, what it came down to is a very simple concept that the team embraced beautifully,” says McClure. “There was no value either in that environment or in any of the interactions that they could give the bears that exceeded what they were achieving by swimming.” So how could they shift the polar bears’ behavior away from endless circle-swimming? By changing the ways in which they created value for the bears elsewhere in the yard, on land, behind the scenes, and in the opportunities available to them. The team accomplished this thoughtfully and creatively, in many ways, and the polar bears responded.

“We looked at the situation as an equation, we changed the way we were thinking, the team embraced it, and within a month or two both polar bears were behaving more positively than anyone could have imagined,” says McClure.

Seal the Deal

One way that the team focused the polar bears’ interest and curiosity on something other than swimming was through a new enrichment opportunity dubbed “Seal the Deal.” In its own zoo-like way, Seal the Deal enabled the bears to simulate hunting a seal at a breathing hole in the Arctic ice. In its first iteration, it was keeper-directed, and in fact Fahy-directed. (At the time, Fahy was a keeper on the bear team and Golden was consulting for the Zoo but still employed elsewhere.) In its final iteration, with Golden’s involvement, it became fully automated so that each bear could “hunt” whenever she chose. (And it will be the first of many automated enrichment opportunities at the Zoo, because Golden is now on board full-time and has plenty more creative engineering ideas where that one came from.)

When a wild polar bear is hunting in the Arctic, it must learn to sit motionless beside a hole in the sea ice for hours and sometimes even days at a time, waiting for a seal to pop up for a breath of air. Then, the bear must strike with lightning speed to grab the seal in its jaws before the seal disappears underwater again. With Seal the Deal, Fahy – while hiding out of sight – would extend a piece of food through one of several opaque tubes toward the participating polar bear. (Each bear had her own solo opportunities to “hunt.”) The bear had to focus intently, remain motionless, and wait for the “seal” to appear at the end of the tube. If she moved too soon, it never “surfaced.” If she were patient, though, it would appear and then she would have to grab it. Sometimes she was quick enough, sometimes she wasn’t, but she got better and better with practice.

“We found that both bears learned faster than we expected and just kept improving their technique,” admits Golden, “so we needed to keep tweaking in order to constantly challenge them.”

This raises an interesting thought: the polar bear is challenging the people to continue to challenge her. She is directing her own enrichment through her behavior. This is an exciting prospect, and it is fundamental to the Zoo’s new behavior program. Let animals show what they value through their behavior. Communicate that information to animal care staff in order to sharpen their insight and enhance their perspective. Support them in this way so that they, in turn, are better positioned to support and enrich the lives of the animals in their care.

BACK TO STORIES

BACK TO STORIES

MORE ZOOGRAM STORIES

MORE ZOOGRAM STORIES