By Sarah Evans

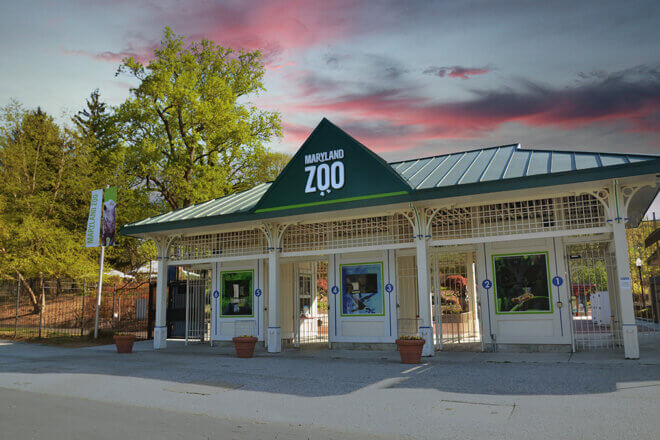

Early one morning last May, Kyle Baumgartner and Marietta Cox – Area Manager and Keeper on the Zoo’s Maryland Wilderness team – stood on the shore of a quiet, beautiful lake in central Iowa. They were there to participate in the release of five young trumpeter swans, one of which had hatched at the Zoo in 2016. The early morning calm was pierced by the excitement of school children, reporters, and others on hand for the occasion, but the swans remained cool. “I was probably more nervous about all the people than they were,” admits Cox.

After a few words of introduction from Dave Hoffmann, a biologist with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources who leads the state’s Trumpeter Swan Restoration Project, the school kids lined up to create a human funnel down to the water. Keepers from the five zoos where the swans had hatched, including Cox, crouched with swans in hand. The countdown began, and the birds were released. “All five booked it into the water,” recalls Cox. “They ran with their wings out, trying to get up a little speed. Our swan actually made it into the water faster than any other!”

As the ceremonial send-off ended and the crowd began to disperse, Baumgartner and Cox stayed on shore watching the swans. The young trumpeters swam off together, away from the people and all the commotion, exploring their new surroundings. They began to bathe and to forage for food. Over the summer, they would learn to fly on this lake. Come fall, they will migrate to wintering grounds filled with other trumpeter swans but hopefully they will return next spring, and every spring thereafter, to this lake and eventually mate, nest, and raise cygnets of their own here.

This May morning marked the start of their life in the wild.

A Conservation Success Story

For Dave Hoffmann and everyone invested in Iowa’s swan conservation effort, the day marked another step in a 25-year quest to bring a native species back to the state and to a region of the country where, centuries ago, it had been plentiful. The story of trumpeter swans in North America is one of near extinction and remarkable comeback. The large, snow-white waterfowl once nested over most of the continent but disappeared steadily as settlers pushed west. The conversion of wetlands to farms and fields, combined with relentless hunting of the swans for their meat, feathers, and skins, pushed them to the brink of extinction by the end of the 19th century. As of 1935, less than 70 trumpeter swans were known to live in the continental U.S., all in southwestern Montana.

Fortunately, however, the species received federal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. A ban on hunting and careful management of the Red Rock Lakes flock (the Montana swans) launched the steady comeback of trumpeter swans. By 2015, there were an estimated 63,000 trumpeter swans living in North America, with about 28,000 in the continental U.S. Those numbers continue to grow as reintroduction and habitat restoration efforts persist in many parts of the country, including Iowa.

The Maryland Zoo is eager to support these efforts however it can. When asked by the AZA’s Trumpeter Swan Species Survival Plan (SSP) to contribute cygnets to the Iowa project, the Zoo readily agreed. As it happens, the Zoo is home to a pair of trumpeter swans that have formed a strong bond, nested successfully for several years in a row, and proven themselves to be able and dedicated parents. The Zoo’s first swan was released in Iowa last spring. A second Zoo swan will be released in Iowa next spring. This year’s cygnet, as swan chicks are called, spent the summer on the Farmyard pond with its family, preparing for a future life in the wild.

Preparing for Life in the Wild

So what does that mean, exactly? It means that since this year’s cygnets hatched out in May, Maryland Wilderness keepers have remained very hands off and have deferred to the parent swans to rear their offspring. This management strategy is not without risk, as it exposes cygnets to possible predation and other natural dangers. However, it is the only way to get them ready for life in the wild.

“They need to learn from their parents how to forage on a large open pond, how to protect themselves, what to do to fend off predators,” explains Jen Kottyan, the Zoo’s avian collection and conservation manager. “If we were to hand-rear them, they would not learn from their parents how to be a swan and they would never survive in the wild.”

This year and last, the Zoo’s swans produced a clutch of five cygnets. Not all survived, but those that did have been parented well. This includes superior protection. “Dad is absolutely amazing,” says Kottyan. “When we go anywhere near that pond, he’s got his wings out, he’s calling, he’s hissing, he’s running at you.” And it’s not just humans he’s willing to confront. “A frog surfaced from the bottom of the pond one day,” recalls Kottyan, “and I saw Dad hightail it across the water and start striking at it while Mom got all the cygnets out of the water.”

The cygnets fall right into line, on land and in water, and mimic their parents’ behavior. They swim, they preen, they skim the surface of the pond for aquatic insects, they eat plants, and they forage for bugs in the grass. They also stick together as a family and have learned to defend themselves. Even when they were smaller than mallard ducks, they felt every bit the trumpeter swan. “If you went near them, they would stretch up tall, they would open their bills, and they’d be hissing,” Kottyan proudly recalls.

Give them time to reach full size, and this defensive behavior will be truly intimidating. Adult trumpeter swans are the largest birds in North America and the largest swans in the world, with few natural predators. They are beautiful to behold, and powerful. Given the chance, they take care of themselves, as history is proving. The Zoo looks forward to this year’s cygnet getting that chance when it joins its wild flock in a few short months.

Share this article